An investigation into the collapse of a 17-story concrete high-rise under construction at 2000 Commonwealth Avenue disclosed a number of irregularities and deficiencies, including, among others:

- Lack of proper building permit

- Insufficient concrete strength

- Insufficient length of rebars

- Lack of proper field inspection

- Various structural design deficiencies

- Improper formwork

- Premature removal of formwork

- Inadequate placement of rebars

- Lack of construction control (Kaminetzky 1991)

Four workers were killed and twenty injured. Fortunately, the collapse occurred slowly enough for many of the workers to escape. The collapse occurred on January 25, and low temperatures had certainly retarded strength gain. Cores showed concrete compressive strengths as low as 700 psi (Kaminetzky 1991, Feld and Carper 1997).

Complete case study by Suzanne King:

On January 25, 1971, two-thirds of a 16-story apartment building collapsed while under construction at 2000 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, MA. Four workers died after a failure on the roof instigated a domino-like collapse all the way to the basement, where the men were found. Fortunately, the collapse took a long enough time for most of the workers to run to safety. This paper investigates the numerous causes and lessons learned of this structural failure.

Introduction

Studying structural failure case studies is a way of studying the history of the engineering profession. Typical calculations for design are based on predicting and avoiding failure. The factor of safety is used to avoid failures, but knowledge of past failures will better equip an engineer to steer clear of future failures. It is not only important to know what caused the failure, but also to understand how it occurred and how to avoid the problem in the future.

In the collapse at 2000 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts on January 25, 1971, punching shear failure is believed to have triggered the collapse of two-thirds of the 16-story concrete building during construction. But an investigation called for by the mayor proved that there were many flaws in the design of the apartment building. It is important to remind engineers of past failures, such as this one so that history does not repeat itself.

Design and Construction

The high-rise apartment building was made of cast-in-place reinforced concrete flat slab construction with a central elevator shaft. This style of construction is popular for multi-story buildings because it requires a minimum slab thickness and reduces the overall height of the building (Feld and Carper 1997). 2000 Commonwealth Ave. was designed to be sixteen stories with a mechanical room above a five-foot crawl space on the roof. The structure also had two levels of underground parking. A swimming pool, ancillary spaces, and one apartment were located on the first floor and one hundred thirty-two apartments were on the second through sixteenth floors. Originally these apartments were to be rented, but the owners later decided to market them as condominiums.

Construction began on the site late in the fall of 1969. Excavation had been partially started a few years earlier. Most of the work was subcontracted to area specialists. Only one representative from the General Contractor was on site during construction. At the time of the collapse, construction was nearing completion. Brickwork was completed up to the sixteenth floor and the building was mostly enclosed from the second to fifteenth floors. Plumbing, heating and ventilating systems were being installed throughout various parts of the building. Work on interior apartment walls had also started on the lower floors. A temporary construction elevator was located at the south edge of the building to aid in transporting equipment to the different floors. It is estimated that one hundred men were working in or around the building at the time of failure (Granger et al. 1971).

Collapse

After interviewing many eyewitnesses, the mayors investigating commission concluded that the failure took place in three phases. These phases were punching shear failure in the main roof at column E5, a collapse of the roof slab, and, finally, the general collapse.

Phase 1: Punching Shear Failure in the Main Roof at Column E5

At about ten in the morning, concrete was being placed in the mechanical room floor slab, wall, wall beams, and brackets. Placement started at the west edge and proceeded east. Later in the afternoon, at about three o’clock, most of the workers went down to the south side roof for a coffee break. Only two concrete finishers, Mr. Daniel Niro and Mr. Joseph Oliva, remained on the pouring level near line 4-1/2. Shortly after the coffee break, the two men felt a drop in the mechanical room floor of about one inch at first and then another two or three inches a few seconds later. The labor foreman, Mr. Anthony Paolini, was directing the crane carrying the next bucket of concrete. He instructed the operator to “hold the bucket” and went down to the sixteenth floor by way of a ladder in the east stairway. That is when the punching shear was noticed around column E5. The carpenter foreman, Mr. Antonio M. Fantasia, was also in the area and immediately yelled a warning to the men working on the sixteenth floor and roof of a possible roof collapse. The slab had dropped five or six inches around the column and there was a crack in the bottom of the slab extending from column E5 toward column D8. Column E5 is located directly below where the concrete was being placed for the mechanical room floor slab on the east side of the building as shown in the following figure (Granger et al. 1971).

Phase 2: Collapse of the Roof Slab

After hearing Mr. Fantasia’s warning, most of the workers in the area of column E5 managed to run to an east balcony and stay there until after the roof slab collapse. Eyewitness testimony concluded that the collapse happened fairly quickly. The roof slab began to sag in the shape of a belly and reinforcing steel started sticking out from the mechanical room floor slab. Soon everything started to shake and the east half of the roof slab collapsed onto the sixteenth floor. Then it stopped, giving the workers a chance to run down the stairs to the ground. At the time of failure, the Structural Subcontractor was placing reinforcing steel for the stairs on the fourteenth and fifteenth floors on the east side of the building. So when the workers were making their way from the roof and floors above, most of them crossed over to the west side of the building when they reached the fifteenth floor. (Granger et al. 1971)

Phase 3: General Collapse

After the roof collapsed, the roof settled and most of the stranded workers could be rescued using the crane and construction elevator. However, about twenty minutes after the roof failed, the east side of the structure began to collapse. A resident of 1959 Commonwealth Ave. described the collapse as a domino effect (or progressive collapse). The weight of the collapsed roof caused the sixteenth floor to collapse onto the fifteenth floor, which then collapsed on the fourteenth floor, and so on to the ground (Litle 1972). At first, the different floors were distinguishable, but later dust and debris made it difficult to discriminate between the various floors. When the dust finally settled, two-thirds of the building had collapsed. The east side and areas on either side of the elevator shaft were gone. Four workers were killed during the collapse and thirty workers suffered injuries (Granger et al. 1971).

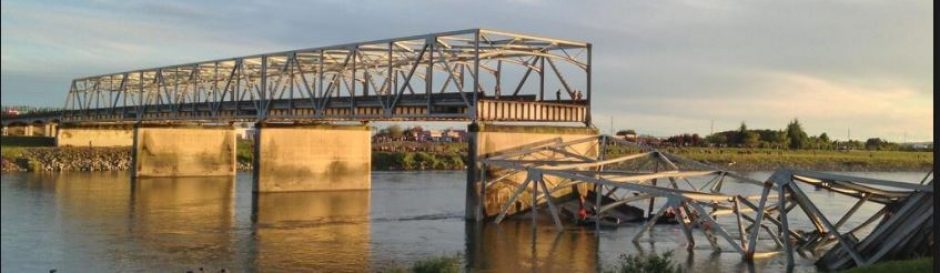

The extent of the collapse is shown in the photographs in APPENDIX B. The first picture is from the February 4, 1971, issue of EngineeringNews-Recordd. This picture shows the floor slabs hanging from individual floors. Only the west side of the building remains standing. The next photograph is a close-up of the collapse. It shows the exposed elevator shaft. The building collapsed around the interior elevator.

Causes of Failure

A week after the collapse, Engineering News Record reported that there were three possible causes of structural failure under investigation: formwork for the penthouse floor slab collapsed onto the roof, a heavy piece of equipment fell from a crane and started the progressive collapse or concrete placed during previous cold days had failed (ENR, February 4, 1971). However, after an extensive investigation, the mayor’s commission concluded that there were many design and construction flaws that attributed to the collapse. The committee determined that punching shear failure at column E5 triggered the initial collapse. This type of failure is caused by unbalanced moments transferred between the column and flat-plate (Megally and Ghali 2000) and was a result of non-conformities to the design documents. The major areas that construction did not follow the design were shoring and concrete strength. Inadequate sharing under the roof slab on the east side of the building made it impossible for the roof to hold the freshly placed concrete for the mechanical room floor slab, construction equipment and two boilers that were stored on that side of the building. Also, the concrete strength of the roof slab was well below three thousand pounds per square inch as specified in the design. However, there were many other factors, design and procedural, that contributed to the collapse (Granger et al. 1971).

Design Concerns

The design concerns that contributed to the collapse include insufficient length and placement of rebar and various structural design deficiencies. All of the reinforcing steel used was designed to be billet steel, however, a large amount of rail steel was found in columns and slabs on the lower floors. The major difference between rail and billet steel (as described in the Commission’s report) is the ultimate elongation. The average ultimate elongation for rail steel used on the project was just over ten and a half inches as opposed to a little over fifteen and a quarter inches for the billet steel. This variance would effect how the floor slabs reacted to tension forces. Also, the steel was delivered by the supplier in bundles with marks on the steel indicating what the steel was intended for. However, some of the marks used were the same as the marks on the design plans, yet meant something different. For example, the supplier gave marks for number four bars at the south edge of the slab which was identical to marks given on the Engineers placing drawings for top slab bars over column E5 (Granger et al. 1971). There were also design errors in the reinforcement. Some of the bars did not extend long enough into the columns as required by code and placement of bars in some of the slabs was not sufficient to meet the American Concrete Institutes (ACI) code at the time. There was also inadequate design around columns. ACI requires that at least twenty-five percent of the negative slab reinforcement in each column strip pass over the column within a distance of “d” on either side of the column face (Granger et al. 1971). This requirement was not fulfilled.

Procedural Concerns

There were many procedural concerns in the construction of 2000 Commonwealth Ave. Nearly every step of construction was flawed (Kaminetzky 1991). Some of the major concerns include lack of proper building permit and field inspection, premature removal of formwork, and lack of construction control.

The investigating committee determined that if the construction had had a proper building permit and followed codes, then the failure could have been avoided. Since there were numerous problems that all aided to the collapse, deciding whom to hold responsible for the collapse became a difficult feat. Ownership changed hands many times and most jobs were subcontracted. Some of the transactions that took place with Bostons Building Department are listed in the table below (Granger et al. 1971). There was confusion surrounding the project from the start.

Construction did not follow the Structural Engineers specifications for shoring or formwork. Before removal of shores and forms, the concrete must first reach seventy percent of its designated twenty-eight-day strength. It was the commission’s opinion that despite seven-day cylinder tests that said otherwise, the average strength of the concrete in the roof slab was only nineteen hundred pounds per square inch after at least forty-seven days, not the required twenty-one hundred pounds per square inch for removal or the specified three thousand pounds per square inch required after twenty-eight days. There was no inspection or cylinder testing done for the east side of the building, so removal of formwork was based on values obtained from the west side of the building. Furthermore, adequate shoring under the roof slab below the freshly place mechanical room floor slab was not used (Granger et al. 1971).

Finally, there was very little construction control on the site. There was no architectural or engineering inspection of the project and the inspection done by the city of Boston was inadequate. The design plans specifically stated that certain aspects of the project needed to be approved by an architect, yet no architect or engineer was consulted. The Affidavit Engineer and Licensed Builder were also nowhere to be found. Instead, construction was based on arrangements made by the subcontractors. As mentioned before, there was only one representative from the General Contractor and this man was not a licensed builder. He did not direct, supervise or inspect any of the work done by the subcontractors (Granger et al. 1971).

Similarities to Other Failures

The progressive collapse of 2000 Commonwealth Ave. was similar to the structural failures of buildings in Bailey’s Crossroads and Harbour Cay. On March 2, 1973, the Skyline Plaza in Baileys Crossroads, Virginia collapsed while under construction. Like 2000 Commonwealth Ave., premature removal of shoring and insufficient concrete strength were the causes of failure (Woodward et al. 1983). The collapse of the flat-plate Harbour Cay condominium building in Cocoa Beach, Florida on March 27, 1981, was caused by punching shear failure triggered a progressive collapse (Lew et al.1983), much like 2000 Commonwealth Ave. Investigations following the three collapses concluded that both design and construction errors contributed to the cause of the collapse. All three failures could have been avoided if better inspections of materials and construction details were conducted.

| Event Table for Construction of 2000 Commonwealth Ave. Apartment Building | |

| Date | Action |

| November 3, 1964 | First building permit application was filed for a seven-story, eighty-nine apartment building. Bartholomew W. Consentino is listed as the owner and S. S. Eisenberg is listed as the architect. The permit was first refused because building exceeded allowable building height. A later appeal granted the permit on December 24, 1964. |

| May 24, 1965 | Letter filed by W. J. Lamborghini of La Mont Corporation stated that construction of the building had started. Records show excavation was started and the lot was fenced. |

| August 16, 1967 | Notice was given to Mr. Consentino by the Building Department that his permit has lapsed due to unreasonable delay in completing the building. |

| November 20, 1967 | Mr. Consentino filed a new building permit for a fourteen story, eighty-five apartment luxury building, naming George Garfinkle architect. However, the permit was not signed by “the person who is to perform or take charge of the work covered by the permit” as specified by codes. Therefore, the permit was not issued. The application was then deemed abandoned because there was no permit issued within six months of application. |

| July 3, 1968 | A zoning change for the property was obtained by Mr. Harold Katz. |

| December 23, 1968 | Wilfred Fink of Toronto, Canada; Morris Feinstein and Theodore Hurwitz, both of Montreal,Canada; and Arthur Haffer, Bartholomew W. Consentino, Harold Katz, Stanley H. Rudman, and Lewis G. Pollock, all of Massachusetts, are named owners of the property at 2000 Commonwealth Ave. |

| July 7, 1969 | A permit was issued for a sixteen-story reinforced concrete building designed by the architectural firm of Webb, Zerafa and Menkes of West Toronto, Canada. However, Massachusetts state laws require permits to bear the seal of a registered architect or registered professional engineer from Massachusetts and the architectural firm of Webb, Zerafa, and Menkes does not have any principal or employees in Massachusetts. |

| August 1, 1969 | An excavation permit is issued to B. W. Consentino as the authorized agent for the owner and Toulon Construction Co. as contractor. |

| August 27, 1969 | Another building permit is applied for, this time naming Jack Palevsky as Owner or Authorized Agent and Toulon Construction, Inc. as contractor. Also, thesignature of Dante F. Montouri of Cochituate, MA appeared in the space for the signature of a licensed builder. It is later revealed that Mr. Montouri was not a licensed builder at the time. |

| August 29, 1969 | A sworn affidavit states that the structural plans, drawn by M. S. Yolles and Associates, were in accordance with the Building Codes of the City of Boston. |

| September 4, 1969 | There is a change of ownership. Two of the previous owners drop out and three more join the existing owners, called the 2000 Commonwealth Associates. |

| September 5, 1969 | The building permit is granted. However, the mayor’s commission’s report describes many irregularities and discrepancies with this permit. |

| Fall 1969 | Construction begins on sixteen-story apartment building |

| Fall 1969 to 1970 | Concept of the building is changed. The owners will now sell the apartments as condominiums. A brochure is made, but no units are sold. |

| November 10, 1970 | Ownership changes yet again. This time Milton Adess, Bartholomew Consentino and Larry L. Webb are made trustees of the 2000 Commonwealth Association Trust. |

References:

- Feld, J., and Carper, K. (1997). Construction Failure. 2nd Ed., John Wiley & Sons, New York, N. Y

- Granger, R. O., Peirce, J. W., Protze, H. G., Tobin, J. J., and Lally, F. J. (1997), The Building Collapse at 2000 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts, on January 25, 1971, Report of the Mayor’s Investigating Commission, The City of Boston, Massachusetts.

- Kaminetzky, D. (1991). Design and Construction Failures: Lessons from Forensic Investigations. McGraw-Hill, New York, N. Y.

Illustrations from Chapter 5 of the book Beyond Failure: Forensic Case Studies for Civil Engineers, Delatte, Norbert J., ASCE Press.