The quality of concrete construction is important, particularly in cold weather. The September 30, 1911, failure of a concrete gravity dam in Austin, Pennsylvania, claimed between 50 to 149 lives. Greene and Christ (1998) put the death toll at 78. It occurred less than 150 miles north of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, 22 years after that more widely known disaster (see Jamestown Flood).

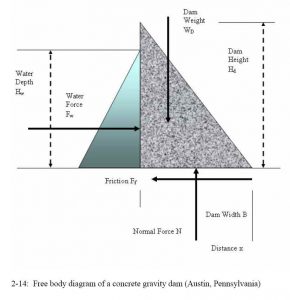

The Bayless Pulp and Paper Mill decided to replace a smaller dam with a larger dam in 1909 to increase production. The new dam was a gravity dam, designed to hold back the water by its mass and friction against the foundation. Cost and time constraints led to pressures to complete the dam before winter. The dam blocked the Freeman Run Valley and was 161 m (530 ft) long at the base and 166 m (544 ft) at the crest. The dam was 15 m (49 ft) high at the crest and 13 m (42 ft) high at the spillway, and 9.8 m (32 ft) thick at the base and 0.76 m (2.5 ft) thick at the crest. The reservoir filled half of the valley and was designed to hold 750,000 cubic meters (200 million gallons or 613 acre-feet) of water (Freiman and Schlager 1995b, pp. 205 -206).

The dam was built from 12,200 cubic meters (16,000 cubic yards) of cyclopean concrete. The cyclopean concrete consisted of boulder-sized pieces of native sandstone rock, bound with more conventional cement and concrete. Twisted steel rods 32 mm (1 in) in diameter, 7.6 m (25 ft) long, were spaced 0.8 m (2.7 ft) apart to reinforce the dam. An earth fill embankment 8.2 m (27 ft) high, sloped 3 horizontal to 1 vertical, was rolled against the upstream face of the dam (Freiman and Schlager 1995b, p. 207).

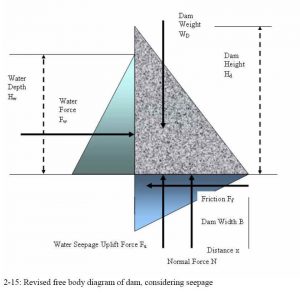

The dam’s foundation was the rock of the valley floor, which consisted of thin layers of shale between narrow layers of sandstone. About 6,000 cubic meters (8,000 cubic yards) of soil was excavated at the foundation, and loose material was washed and cemented together with grout. A 1.2 by 1.2 m (4 by 4 ft) footing extended into the bedrock, and the abutments were also cut 6.1 m (20 ft) into bedrock (Freiman and Schlager 1995b, p. 207).

The dam was not yet finished as winter approached, and the last hurried concrete construction was carried out with temperatures below freezing. By December 1, 1909, when the dam was completed, a large crack passed completely through the dam, fracturing some of the cyclopean boulders. A second crack appeared later that month. With the dam empty, and no visible settlement of the foundation, it appeared that the cause was a contraction of the concrete (Freiman and Schlager 1995b, pp. 207-208).

The dam reservoir was filled within about six weeks of completion. On January 17, 1910, a combination of heavy rain and snowmelt due to warm temperatures put flood water over the spillway. Heavy seepage near the toe of the dam and cracks on the downstream face of the dam was observed. To lower the reservoir, Bayless used dynamite to blast two notches in the dam crest. Superficial repairs were made to the dam after the water level dropped, and then the water level was allowed to rise to the normal pool again (Freiman and Schlager 1995b, p. 208).

During this event, the dam developed six prominent vertical cracks, and the top center of the dam bowed 0.76 m (30 in) downstream. The dam had been built without construction joints, so the cracks divided the dam into seven separate segments. The blasting had been necessary because the dam had no spillways or gates to allow controlled water release (Greene and Christ 1998, p. 9).

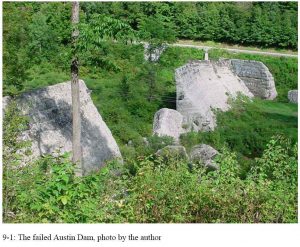

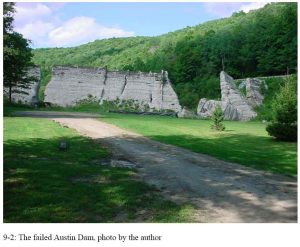

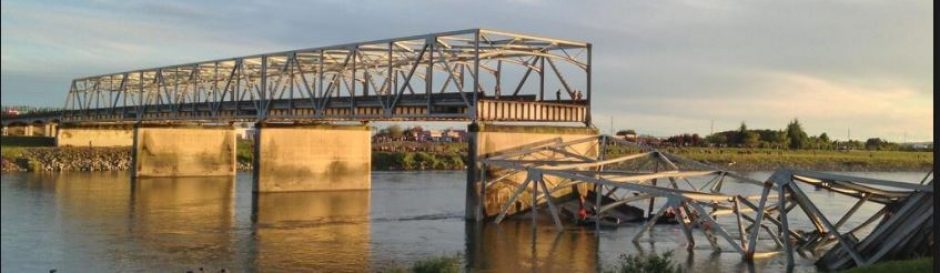

The dam failed on the afternoon of Saturday, September 30, 1911. A hole opened at the west abutment, and the force of the water pushed out the blocks of concrete which slid downstream. The water channeled as a large wave between the high vertical valley walls as it smashed into the town of Austin (Freiman and Schlager 1995b, p. 208).

Like the South Fork Dam responsible for the Johnstown Flood, the Austin Dam did not have pipes or any other means to rapidly reduce the water level in case of danger. The remains of the dam are still visible today along Pennsylvania Route 872, north of the town of Austin.

References and Sources

The complete case study is provided in Chapter 9 of Beyond Failure: Forensic Case Studies for Civil Engineers. This case is discussed by Freiman and Schlager (1995b, pp. 205 -212). Another source is Greene, B.H., and Christ, C.A. (1998), Mistakes of Man: The Austin Dam Disaster of 1911, published in Pennsylvania Geology.

Freiman, F.L., and Schlager, N. (1995b) Failed Technology: True Stories of Technological Disasters, Volume 2, UXL, Gale Research Inc., an International Thompson Publishing Company.

Greene, B.H., and Christ, C.A. (1998), Mistakes of Man: The Austin Dam Disaster of 1911, Pennsylvania Geology, Vol. 29, No. 2/3, pp. 7-14, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Summer/Fall 1998, online at https://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/topogeo/pub/pageolmag/pageolonline.aspx

Illustrations from Chapters 2 and 9 of the book Beyond Failure: Forensic Case Studies for Civil Engineers, Delatte, Norbert J., ASCE Press.